|

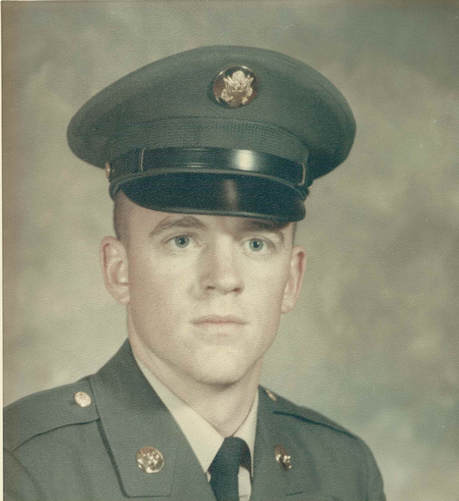

FNG or “F***ing New Guy” was a label given to new replacements because an FNG was dangerous; he could get you killed. The veterans shunned an FNG. The “F” part of the label was derogatory and meant to be. So it became the goal of each FNG to lose the “F” in the label first. An FNG needed to prove himself to his squad and platoon members. To know what an FNG is you need to understand the hierarchy within a squad and platoon. We all arrived to our unit as an FNG and had 365 days before we could go home. The platoon members who were in the platoon longest were “old timers” or “short timers.” They had a wealth of experience and were going home soon. Their experience is what could save an FNG’s life. The FNG needed to carry his weight, listen, and learn. He couldn’t be a know-it-all. His accomplishments in the “world” weren’t important; they did not matter in Vietnam. No one cared if the Army drafted you, you went to college, or were a high school star quarterback. This was Vietnam! You had to be trusted to pull your guard duty with no one worrying if you were inattentive or asleep. Their lives depended on you being alert and awake. While writing this, one FNG from first platoon stands out. On or about August 7, 1969 the supply chopper landed as we prepared for the evening, and an FNG jumped off and moved to the Command Post (CP) position. Lieutenant Baxter brought the new guy over and introduced him to Jerry Ofstedahl, second squad leader. The new guy was Tommy Thompson from Bristow, Oklahoma. Jerry introduced Thompson to the rest of the squad. As Jerry introduced Thompson, several of us made eye contact and nodded our head at him. A couple squad members stood and shook his hand. But it was business as usual, and we didn’t have time for an FNG. Tommy Thompson Basic Training Photograph One week later, August 15, 1969, Tommy Thompson was critically wounded and placed on a dust-off helicopter. He was medevac’d to the Division hospital in Chu Lia and never returned to the platoon. He never had the “F” dropped from the FNG label. If I have the power to do so, Tommy, the “F” is hereby dropped.

2 Comments

By Glyn Haynie

The first five parts of The Vietnam War, a documentary by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, aired Sunday through Thursday this past week. Each evening at 7PM I settled into my recliner to watch the PBS channel wanting to see if the documentary gives the soldiers that fought in Vietnam, now the Vietnam Veteran, the appreciation and welcome home they so deserve. The basics of French involvement and withdrawal from Vietnam are well-known to the American soldier. In the first couple of episodes I learned underlying facts about the politics that led up to the war and the politics that got the United States committed to war. As I watched, it amazed me that the French people shouted disparaging remarks at their French soldiers and pelted them with rocks when they came home from war. The French government and citizens showed no appreciation for their service to country, however politically misguided. Sound familiar? Both Presidents Kennedy and Johnson privately showed the moral compass of the right thing to do: not get involved, but they followed their political instincts instead. What shocked me most was our President, with a few advisors, committed us to fight a war. Year after year, a president and his advisors, continued to make decisions that resulted in our involvement and the deployment of increasing numbers of combat soldiers. What happened to the Declaration of War that unites and commits the country and people of America to fight a war? Prior to the documentary’s video of the mid-60s, my memories of Vietnam played in black and white, incomplete and distorted. When Ken Burns showed 1966 and 1967 television footage, my memory was immediately restored to vivid color, and blank spots lost over the years were filled in. I found it very difficult to watch the fire-fights, the wounded, the dying and the dead. I had to fight back tears and try to control the emerging fear I had brought home from the war and hid away for decades. I thought I had tamed the beast, fear! I wanted to get up and leave the room. Now I knew how difficult it would be to continue watching the documentary, but I am committed to watch through the final episode. I am disturbed, actually more than disturbed, that Ken Burns and Lynn Novick are showing the faces of the American and Vietnamese soldiers wounded and dead, even worse at the point of being killed. The media did the same during the war, showing the American people the war through an unfiltered lens. I don’t say this to hide what war looks like but what about the mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, sons, daughters, wives and girlfriends that watch? Must they again see their loved one wounded or killed on the battlefield? Are ratings more important than respect to the soldiers on both sides of the war? I will try to use this time to pull myself back together. I will sit in my recliner ready to watch the next five parts, beginning Sunday at 7PM. I know the next several episodes will be even more difficult. I’m almost ready, not really. After completing basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, Infantry Advanced Individual Training (AIT) at Fort Gordon, Georgia, and attending airborne school (did not complete) at Fort Benning, Georgia, my brother Wayne and I received orders for a 12 month tour in Vietnam. We went home to begin our 30-day leave before reporting to Fort Lewis, Washington and subsequent processing to Vietnam. Glyn Haynie Basic Training Aug 1969 Glyn, on left, and Wayne Leaving March 9, 1969, Wayne and I left our parents’ house for Vietnam. My mother, father and sister took us to the Columbus, Georgia airport, and we said our goodbyes. We boarded our flight and flew to Fort Lewis, Washington, the first stop on a long journey. We spent one night at Fort Lewis and the next morning we boarded an international flight to Vietnam with stops in Alaska and Japan. Wayne and I sat next to each other the entire flight. Our first assignment was the Americal (23rd) Infantry Division Combat Center at Chu Lai. The army didn't know what to do with two brothers in-country so they kept us at the Combat Center until someone finally made a decision. After six weeks Wayne went to Korea, and I reported to First Platoon, Company A, 3rd Battalion/1st Infantry, 11th Brigade, Americal Division. Wayne Haynie, April 1969, at the Combat Center in Chu Lai. Just finished cleaning gear. If I remember correctly our hooch would be to his left. The Combat Center was located on the Americal Division firebase in Chu Lai. To your right of the sign is the "Shipping Shed" where replacements reported to go to their units.

By Glyn Haynie Yes, I am a Vietnam Veteran! I served a year in Vietnam as an Army infantry soldier with First Platoon Company A 3rd Battalion/1st Infantry 11th Brigade Americal (23rd) Infantry Division and served in the U.S. Army for twenty years. I told myself over and over again I would not get vocal about the Ken Burns documentary ”The Vietnam War.” Heck, it has not even aired yet. BUT I watched some interviews on television and the internet, and emotions surfaced that I didn’t know existed. At first I didn’t understand why, but then realized I am fearful that the American soldiers who fought the war and now the Vietnam Veterans will still not get the fair treatment or positive recognition they deserve. Will we still have to go on thinking we should be ashamed of our service? The American public doesn’t know or maybe doesn’t care how the Marines, Soldiers, Airmen and Sailors who came home from fighting a war—for the American people and our country—were sometimes abused and ignored because of their service. The politics of the war don’t matter, then or in hindsight— American youth took the oath to support and defend, and that is what we did. The Greatest Generation took the same oath in World War II. I am not saying the Baby-Boomers compare to the Greatest Generation, but I will say every soldier I served with in First Platoon was just as dedicated and brave as the generation before us. They were the Greatest of Our Generation! Most did not complain about the politics of the war or question why we were there. They endured the heat, rain, food, being dirty, hungry and scared as hell; that’s what good soldiers do. I have three sons who served and returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. After returning, my two youngest, both infantry soldiers, asked how I processed and stored the memories of my Vietnam experiences. My only advice was that I put the memories in a box and stored it away. Probably not the best advice a father can give his sons, but that’s what Vietnam Veterans did. Heck, I was even envious of my sons because of the Welcome Home they received. How sad is that! What’s even sadder, other than my petty envy, is how Vietnam Veterans greet each other. It can be anywhere… at the mall, a car wash or restaurant. When two veterans, strangers, greet they first ask each other what year they served, then shake hands and embrace and then say two words to each other: Welcome Home! If you don’t see the irony in this greeting, then you don’t get it. Hopefully the documentary will clear it up for you. I have been asked if I would do it again. My response is always Yes – with the men of First Platoon, the finest and bravest men you will ever meet. To all Vietnam Veterans - Welcome Home Brothers! Ok Ken Burns and Lynn Novick bring on the Documentary and reinforce my pride as a Vietnam Veteran! First Platoon photograph taken at our First Reunion 2016. Sitting, left to right: Gloria Ramos, Maurice Harrington, Mike Dankert, Fred Katz. Standing, left to right: Glyn Haynie, Don Ayres, Cliff Sivadge, Dusty Rhoades, Lesley Pressley, Charlie Deppen, Chuck Council, Dennis Stout, John “Mississippi” DeLoach and Ray “Alabama” Hamilton. Note: Gloria Ramos is the sister of Juan Ramos who was killed July 14, 1969. My three sons returning from war April 2004 - From your left - David (Special Ops), Nathan (82nd Airborne) and Bryan (Ranger Battalion). Although fearful while they were in a combat zone, at one point all three simultaneously, I am extremely proud of their service and accomplishments.

By Glyn Haynie I was assigned to the 1st Platoon Company A 3rd Battalion/1st Infantry 11th Infantry Brigade Americal Division and awarded the Combat Infantry Badge (CIB), along with every other infantry soldier who saw combat in Vietnam, however this is the award I am proudest to wear. This one award speaks volumes about the soldier wearing it. The infantry soldier is a unique breed. As stated by the United States Army Human Resources Command – The Combat Infantry Badge (CIB) was established by the War Department on 27 October 1943. Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair, then the Army Ground Forces commanding general, was instrumental in its creation. He originally recommended that it be called the "fighter badge." The CIB was designed to enhance morale and the prestige of the "Queen of Battle." Then Secretary of War Henry Stinson said, "It is high time we recognize in a personal way the skill and heroism of the American infantry." We did not wear awards in the field and most times no other insignia. Mike Dankert came up with a solution to wear a “CIB”. It was nothing more than a safety pin pinned to the left pocket of his shirt. Others in first platoon adopted the wearing of the “field CIB”. This action is one way we could show how proud of this award we were. Mike Dankert with rear job at the brigade headquarters at Duc Pho. Note the safety pin on his left pocket. He is still wearing it even though he is wearing the authorized CIB worn above the U.S. Army tag.

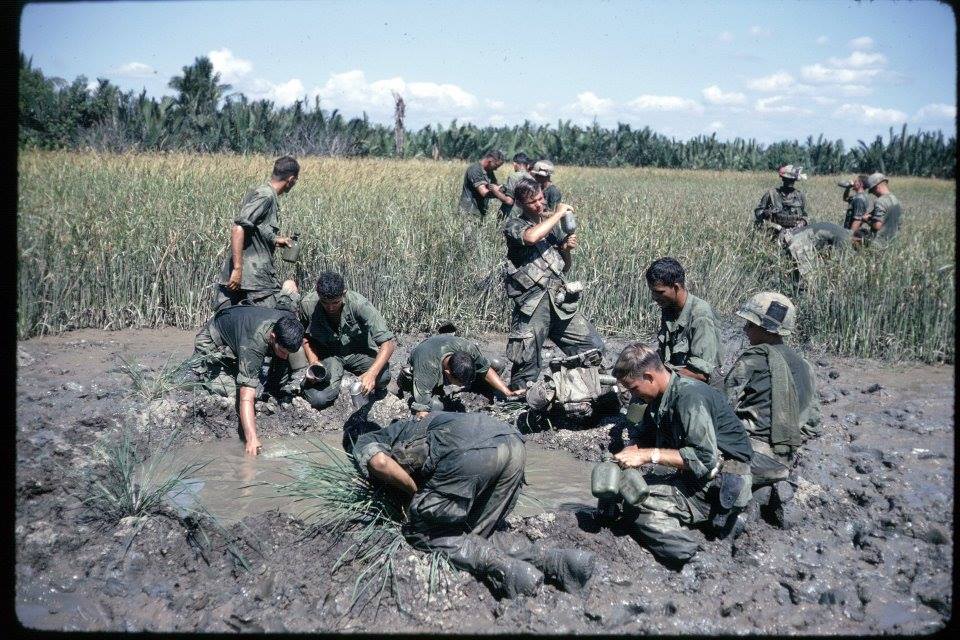

When my son’s came home came home from Iraq and Afghanistan, I took this opportunity to pin my dad’s Combat Infantry Badge (CIB) on Nathan and my CIB on Bryan. Nathan served with the 82nd Airborne Division as an infantry soldier and Bryan served in a Ranger Battalion as an infantry soldier. By Glyn Haynie I found this photograph on the VietnamWarHistoryOrg page, posted by Tom Lacombe, and I thought it illustrated one hardship endured by infantry soldiers (unit unknown). After filling the canteens we would add iodine pills to make the water safe to drink and Kool-Aid to "try" to kill the taste of the iodine and nasty water. We would get water from streams and wells too, and it would taste as bad as this rain water. Look at the uniforms the soldiers are wearing. They are wet and dirty, and most likely soaked with their sweat. It was “normal” for us to wear the same uniform for weeks at a time before getting clean uniforms. Clean uniforms were dropped off in a bundle by a supply helicopter for the platoon, and we would search through the bundle of uniforms trying to find a set that would fit. This is a photograph of Mike Dankert (on your right) and me getting water from a Vietnamese well located west of Quang Ngai. This was a typical way we got drinking and bathing water. If no wells then a stream was the next choice.

|

AuthorWhen I Turned Nineteen Soldiering After the Vietnam War Archives

September 2019

Categories |

Glyn Haynie, Author

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed