|

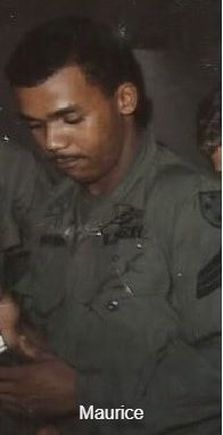

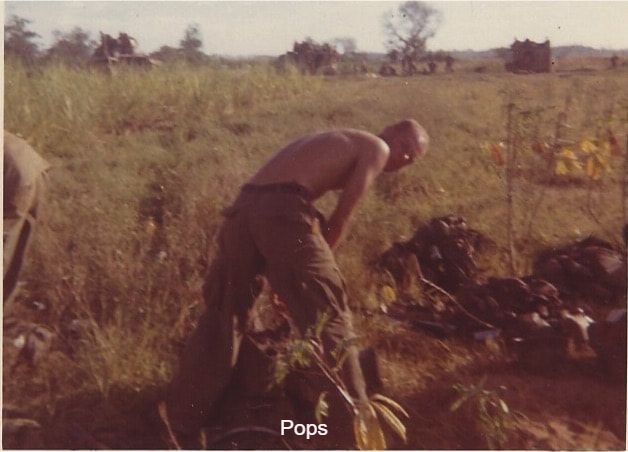

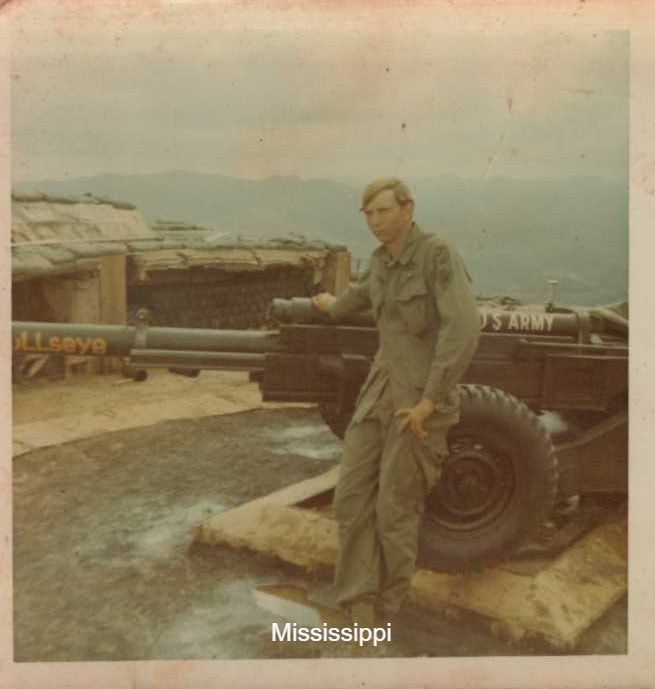

When a replacement arrived at the platoon, the platoon members’ evaluation started right away. One of the veterans’ first topics of discussion was what to call the new guy. We seldom used first names in the army, so addressed everyone by their last names, which was not as much fun as assigning a nickname. There was one exception, Maurice Harrington; we called him by his first name, Maurice. I kept secret the nickname of my school days, Little Haynie, given because of my size compared to my brother Wayne’s size. He was Big Haynie. Honestly, a nickname tells just a little about the individual and seldom is derogatory. Let me give you a few examples: A soldier from Nebraska reported to the platoon in early March 1969, and when asked his name he responded “Rhoades.” Of course his nickname became “Dusty.” Dusty served with the platoon until wounded July 14, 1969. In April 1969 an older, balding replacement by the name of Chuck Council reported to the platoon. Chuck was from Oregon, and at the age of 23 had a college degree. Because of his advanced age and college education Chuck became “Pops.” Pops served in the platoon until he got a rear job as, fittingly, the Education NCO. (Administer GED test and provided information about college.) The last example was a tall, lanky replacement who reported in early June. His name is John DeLoach. Now when I say John was tall, I mean tall. He was six foot two, seven inches taller than me. John had an easygoing manner, a distinctly southern drawl and was from Mississippi. Ronald Owens gave John the name “Mississippi”. John served in the platoon until he moved to an artillery unit. These odd but often obvious nicknames made platoon members more personable and more like brothers and family. They served to help soften the reality that we were not at home, though we cared about each other and looked out for each other.

0 Comments

John William Haynie, my father, was born on June 5, 1924, in Franklin, North Carolina. He died on September 9, 1984, in Center, Alabama, at the age of 60. He entered the Army on March 16, 1944, when he was 19 years old and served in World War II, Company G 157th Infantry 45th Infantry Division. He served in Vietnam in the year 1967 and served with the 199th Light Infantry Brigade. He retired at the rank of Captain after 26 years of service in 1969. Some of his assignments after the war were: Heidelberg, Germany, Fort McPherson, Georgia, Fort Monroe, Virginia, Orleans, France, Vietnam, and Fort Benning, Georgia. Below is an article in the Asheville Citizen-Times newspaper published in 1944 which talks of an action in World War II, with Company G 157th Infantry 45th Infantry Division (the Thunderbirds) that includes my father. Haynie Gives Alarm, Many Jerries Sadder For a little while the Thunderbirds in the little house on the hill were looking down the Jerries’ throats – but only figuratively. There was no doubt in anyone’s mind that the Krauts had the drop on them. The assault company, G, trudged along the road. Directly behind them was 200 yards of blacktop and nothing else. Then came the support companies and a few tanks. To the right of the road was a little house on high ground. Tech. Sgt. Gene Thompson had set up a cannon company OP there, and St. Sgt. Paddy Williams, Durham, N.C., was up there looking around for the mortars. Sgt. Louis Wims, Attleboro, Mass., and Pvt. John W. Haynie, Ashville, N.C., went up to help. One of the four men spotted a couple of figures coming around the bend of the hill below them. No one was quite sure if they were German, but the suspense didn’t last long. Around the bend came about 50 more figures, and there was no mistaking them this time. They were Krauts. They headed for the open stretch of blacktop, intending to cut off Co. G from the support that followed. A few of them stopped long enough to set up a mortar. The four Thunderbirds looked down at the Germans. The 50-odd Germans looked back up at the Thunderbirds. Then Private Haynie made a dash. Across open terrain under the observations of all the approaching Krauts he sped to warn the companies coming up. He made it. His information was relayed to our mortars and machine guns and the Germans were pinned down before they could get off more than a couple of rounds of mortar ammo. Later when Co. A cleaned up the sector, over 70 prisoners were taken. The photograph on the left is Private John W. Haynie, age 19, May 1944 before leaving for WWII, assigned to the 45th Infantry Division. The photograph on the right is Captain John W. Haynie serving in Vietnam 1967 with the 199th Light Infantry Brigade. He lost a lot of weight while there. He was 43 years old when this picture was taken. When I left Vietnam I brought home few of the items I used during my tour. Even when I got to Fort Lewis, I didn’t keep my jungle fatigues or boots. I changed to the Class A uniform that Fort Lewis supply provided and discarded my other uniforms and boots. In hindsight I regret not keeping more of the military and personal items I used that year. I do have the watch I purchased at the Chu Lai Post Exchange, April 1969, and wore during my tour and after I got home. That Seiko watch endured numerous hardships and saw me through many hours of guard duty. Its hands glowed at night making it easier to see the time. For the longest time I thought it did not keep time correctly because by the end of the guard shift it would be 15 to 20 minutes fast. Since my watch had the glowing hands it was often rotated among those on guard duty. I found some platoon members, while on guard, would set the time forward five minutes so they could get off shift and to sleep earlier. Being the last man on guard meant you might have an extra 15 or 20 minutes of guard duty. My battery operated Norelco shaver was a gift from my mother. She gave Wayne, my brother, one too. Mine got little use because I shaved “maybe” once a week just to remove peach fuzz. While building FSB Hill 4-11 our Company Commander, Captain Tyson, got upset because I appeared unshaven. The platoon members who were present all broke out in laughter. Captain Tyson did not see the humor. I wanted a peace-sign necklace but didn’t have cash with me. Paul Ponce, a platoon member, noticed my dilemma, approached the Coke girl, and purchased the necklace for me. I wore the peace sign throughout my tour, and it was my good luck charm. Every time I got scared, which was often, I rubbed it for good luck. It is a reminder of Paul too.

By Glyn Haynie

I am relieved that the documentary “The Vietnam War” has finished. I learned that the government will use a political agenda instead of its moral compass to make decisions, which may not be best for the country. It shocked me to learn the depth of the lies our government told the American people and the criminal acts committed by our government. The most important lesson learned is we, the American people, should force any sitting President to Declare War before committing combat troops. There should never be a President, with a small group of advisors, making the decision about war and/or troop commitment. Generals can’t fight a political war; they need the authority to fight a war as military leaders. We need all elected politicians to stand up and convincingly state whether war is the right action or not. A President can’t go to war without Congress providing the funds. It seems during Vietnam we had a weak and ineffectual Congress. Does that sound familiar? I know many veterans were watching and talking about the documentary, but I wondered what discussion the documentary was creating in my community. When going to stores, restaurants, malls, the car wash and doing all my other daily activities, I asked people of all ages what they thought of the documentary. I believe only one person (in my age group), out of forty or fifty random people, said she was watching the documentary. I guess the conversation is only happening among veterans who served and others in the baby-boomer generation. I found this disappointing. Throughout the years I have fought mixed emotions about protesters and what I felt they stood for during the turbulence of the Vietnam War. I understand and believe in the right to free-speech and to protest against the government. I fought for those rights and served 20 years in the Army to preserve those rights. I tried to stay open-minded about the anti-war movement portrayed during the Ken Burns Vietnam War documentary and to understand why the protesters were so outspoken and, at times, violent. I can grasp the outspoken part, but absolutely do not understand using violence to condemn the men that were fighting or had fought in Vietnam. It has continually confused me even more that protesters’ hatred and violence were often directed toward the men who came home from war. I respect the individuals who genuinely and peacefully protested the war based on their moral values or what they thought was the best course for America. The Vietnam veteran who protested the war was the most sincere protester; he understood what he was protesting. I don’t respect the Vietnam veteran who protested the war because it was the popular choice and therefore offered a jumpstart to a political career. Let’s not forget a famous entertainer who went to a country we were at war with expressly to encourage them. She gave North Vietnam and its army the will to continue fighting against HER countrymen. She went to Hanoi. Jane was her name. It surprised me they showed the video of Jane Fonda saying “POWs should be tried, convicted and executed” while in Hanoi. I believe this speaks of her character and traitorous actions. What about the 30,000—60,000 men who fled, ran, and hid in Canada to protest the war? How can anyone protest something going on in America from Canada? Was it truly a protest statement, or were they thinking of themselves and no one else? Thank you, President Ford for allowing these brave Americans back to “our” country. I would bet that, to a man, they’re now successful capitalists, enjoying the fruits from the sacrifices of servicemen and servicewomen before Vietnam, during and now. President Ford’s amnesty program included 50,000 deserters; these men left their brothers on the battlefield alone, and some died because the deserter was not there. They too are enjoying America today. Let’s hope one doesn’t live next door to you and is needed in a time of crisis. It amazed me to hear and see people in the documentary commenting that going to Canada or deserting their military unit during war was the bravest act they’ve ever done. I can’t believe they actually believe their own statements. Part of President Ford’s amnesty program required the returning deserters and draft dodgers to take an oath of allegiance. Didn’t the deserter already swear to the oath of allegiance when he enlisted? I believe the documentary talked more of their bravery than it did of the American soldier’s bravery. The documentary barely talked of the amnesty program but gave those individuals plenty of air time to talk about their “bravery.” One of the most disappointing segments was the depiction of American soldiers’ drug use and racial intolerance from 1971 and later, as if this was the fault of the military and war. In the early 70s the Army stationed me in Germany with an infantry battalion, and we had the same problems. I believe this to be in direct correlation to the “peace” movement and universities. I believe many universities taught (either directly or indirectly) our youth that doing drugs and demonstrating disobedience to authority were the norms. It wasn’t happening only in Vietnam and Germany; it was happening in the units stationed in Korea too. Of course the “peace” movement need not take responsibility for actions that may put them in a negative perspective nor did the documentary show them in a less than positive way compared to the American soldier. As stated earlier, I have learned from the documentary. However, I am saddened that the American soldier wasn’t portrayed in the same positive manner as the soldiers who fought wars before Vietnam. The soldiers didn’t decide to go to war; our government did. America called its youth to serve, and they served with honor and bravery. Most soldiers never committed an atrocity against a civilian or soldier, but the documentary and John Kerry (his were unauthenticated, second-hand accounts) told us otherwise. The documentary did not give the respect the American fighting men and women earned. For all Vietnam veterans, I am disappointed. |

AuthorWhen I Turned Nineteen Soldiering After the Vietnam War Archives

September 2019

Categories |

Glyn Haynie, Author

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed