|

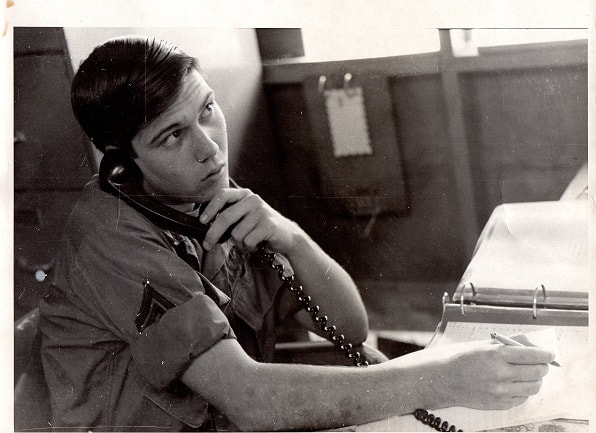

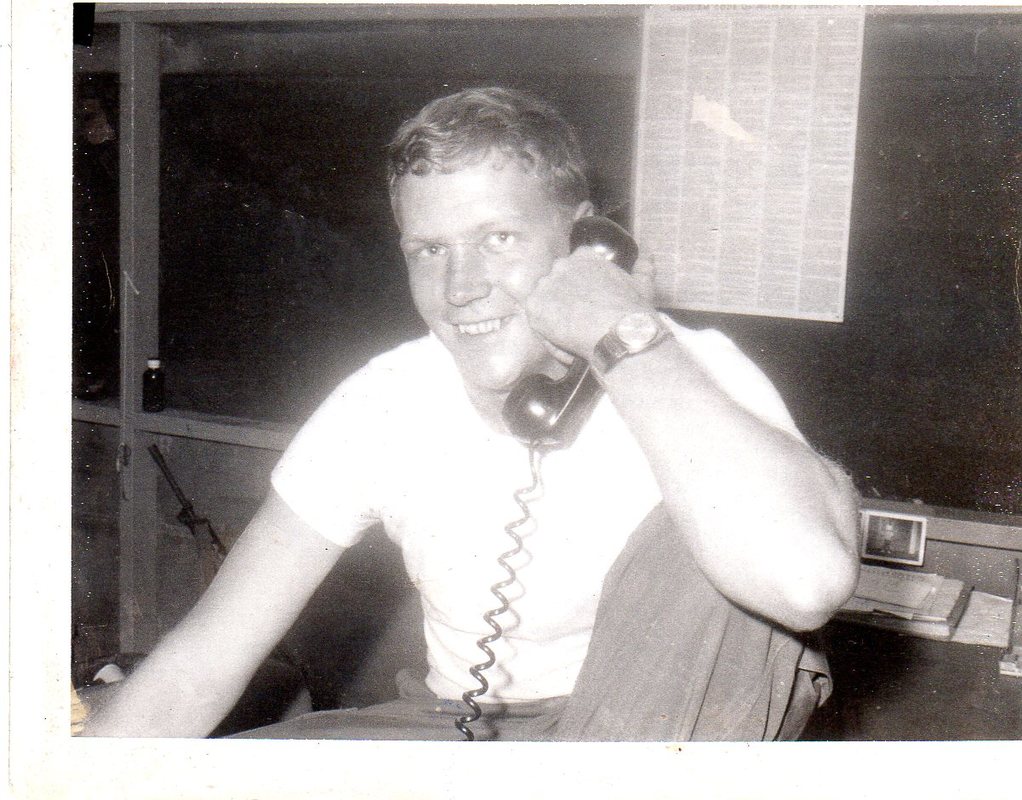

A rear job was a position, usually on a larger firebase, performed without formal training because it was not our assigned military specialty. We started our tour counting down the days from 365 and, in the meantime, hoped to get a rear job. Having a rear job meant leaving the field early, being relatively safe, eating hot food, and living in a hooch with a bed. My rear job was “Shipping NCOIC” working as an administrator at the Americal Division Combat Center in Chu Lai. I was responsible for sending replacements to their units. After Bill Davenport (wounded January 14, 1969) was released from the division hospital, I asked the company commander to have Bill replace me as the Shipping NCOIC; he agreed. We got to spend several weeks together before I left for home. Mike Dankert left the field a couple weeks after me and got a rear job at LZ Bronco, the 11th Brigade FSB at Duc Pho, working in supply. Glyn Haynie Bill Davenport Mike Dankert

0 Comments

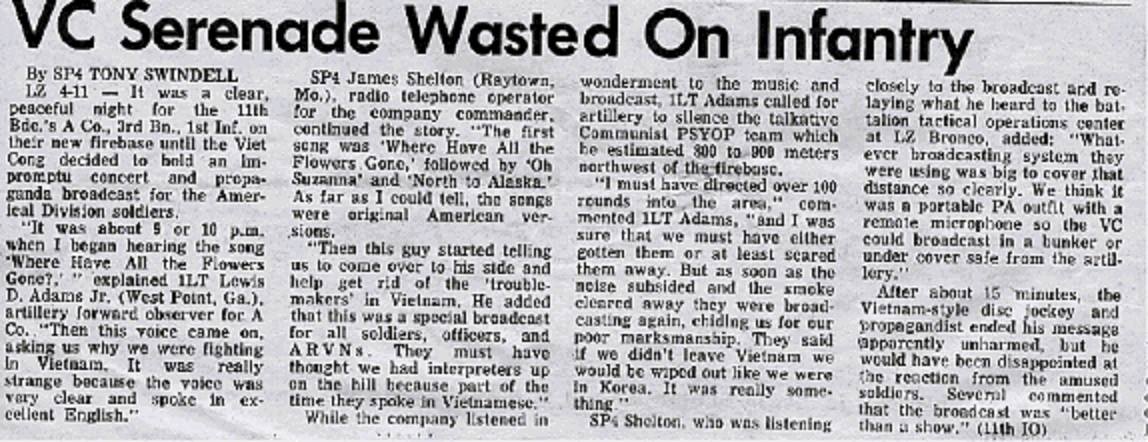

PSYOP - The NVA was more sophisticated than reported; they routinely used Psychological Operations (PSYOP) attempting to wear us down. We were on Hill 4-11 for less than a week with Mike Dankert and I sitting at our position, talking, and drinking Cokes while John Meyer was on guard duty. I was about to say I was ready for bed when, out of nowhere, we heard songs playing from the jungle 800 meters away. Everyone on the Hill got quiet. The three songs played were “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” by Peter, Paul and Mary, “Oh, Susannah” by James Taylor, and “North to Alaska” by Johnny Horton. The sound quality was good.

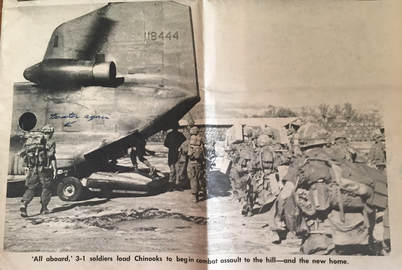

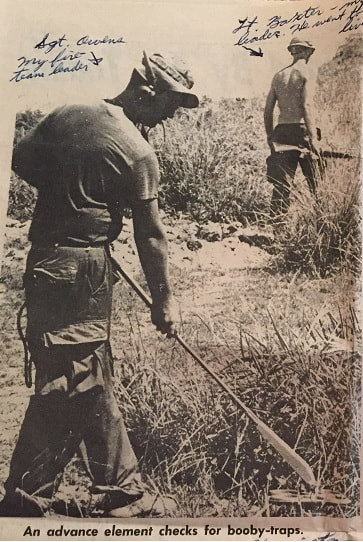

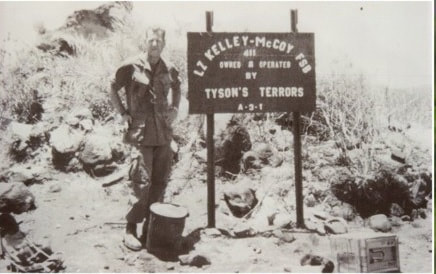

Then the broadcast changed to someone speaking in excellent English asking us why we were fighting in Vietnam. He told us to surrender, come over to their side, or get wiped out. Our unit gave its response, with our artillery opening fire toward the music and voice, making us duck for cover. They fired more than 100 artillery rounds to silence the NVA. Once the artillery ceased firing and through the rising smoke and dust, the voice came back and taunted us for poor marksmanship. Below is the article written by SP4 Tony Swindell assigned to the 11th Brigade Information Office (IO) On this Veterans Day I want to introduce some members of First Platoon - Company A - 3rd Battalion/1st Infantry - 11th Brigade - Americal (23rd) Infantry Division. These are the men I want next to me if called to war. Turn your speaker on and volume up. This “Hill” soon defined our platoon and the Area of Operation (AO) we patrolled. The morning of July 8, 1969, in a column of twos, our platoon entered the rear of the Chinook helicopter. It lifted off, taking us to secure the new firebase location on a hill seven miles west of Quang Ngai City. The Chinook landed without receiving enemy fire, and we exited through the rear door as soon as it dropped. We moved up the hill, encountering many mines and booby traps along its crest. The Company Commander deployed Sergeant Owens with a minesweeping device to sweep the hill for booby traps. We found booby-trapped grenades, 2.75-inch rockets, and a canister full of napalm with a firing device planted in the ground. Lt. Baxter, Alpha Company’s First Platoon Leader, taking a break while the platoon and company start building the new firebase Hill-411. Note the small sandbagged shelter to his top left. Each position had the same shelter. They were all we had until the bunkers were built a week later. Combat Engineers built the bunker shells, and we sandbagged them. Vertical Divider

Vertical Divider

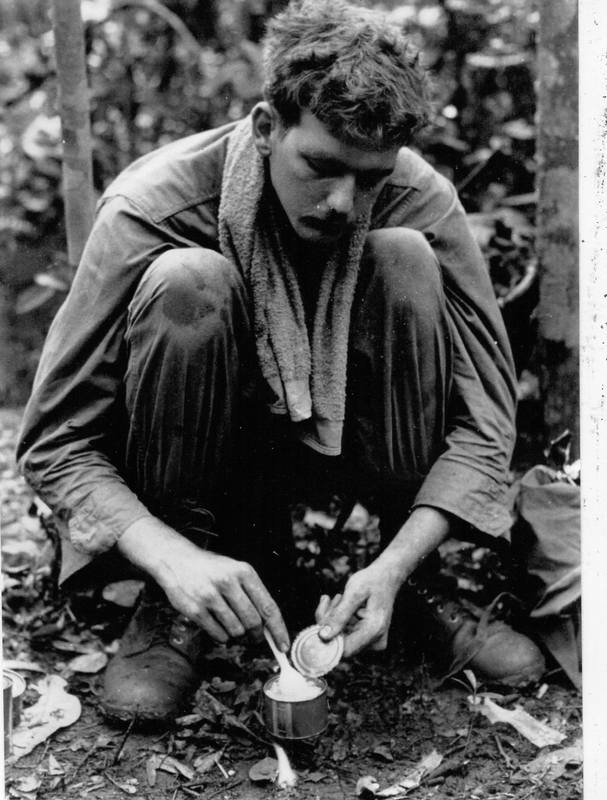

This is another good illustration of infantry soldiers living in the field weeks at a time. This soldier’s unit is the 199th Infantry Brigade, the same Brigade my father served in 1966-1967. He is using C-4 to heat his c-rations. C-4 is a plastic explosive with a texture similar to modeling clay so can be molded into any desired shape. C-4 is stable, and an explosion can only be initiated by a shock wave from a detonator. We each carried a half pound block of C-4 in our rucksacks, using it to heat our rations. The C-4 heated faster and more evenly across the cooking surface than a heating tab. This soldier isn’t using a “stove” to cook his rations. Most of our platoon members used a can opener to punch holes into the bottom edge of an empty c-ration can for ventilation as a makeshift stove. We put the C-4 into the stove, lit it, and placed the can on top. No need to hold the can by the lid. If we ran out of C-4 for cooking, we got some from the inside of a claymore mine. This photograph shows the soldier wearing a uniform and boots that are wet and dirty. Some platoon members wore towels around their necks as protection from the rucksack straps cutting into their shoulders. His uniform does not fit well, with his sleeves too short for his arms. Photograph by combat photographer Art Jaeger We flew by Huey helicopters from one location to another; occasionally we used Chinooks. A Combat Assault (CA) is when the platoon or company loads onto Hueys and flies to a new location expecting enemy resistance. As we approached the Landing Zone (LZ) the door gunners prepped the area with M-60 machine gun fire. When we received enemy fire it was called a “hot LZ,” and we would start jumping from the Huey before the skids touched the ground. This was dangerous because we jumped 3 to 5 feet from the ground with 60 pound rucksacks and weapons. I’m surprised we did not get injured more often. Unknown photographer. The last photograph shows soldiers from the 199th Infantry Brigade crossing a stream. This task is common for infantry soldiers regardless of their assigned unit. The rushing water could carry a soldier downstream or he could get stuck in the mud in the bed of the creek. The leeches were another story. We would stay wet for days on end during the monsoon season. Photograph by combat photographer Art Jaeger.

|

AuthorWhen I Turned Nineteen Soldiering After the Vietnam War Archives

September 2019

Categories |

Glyn Haynie, Author

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed